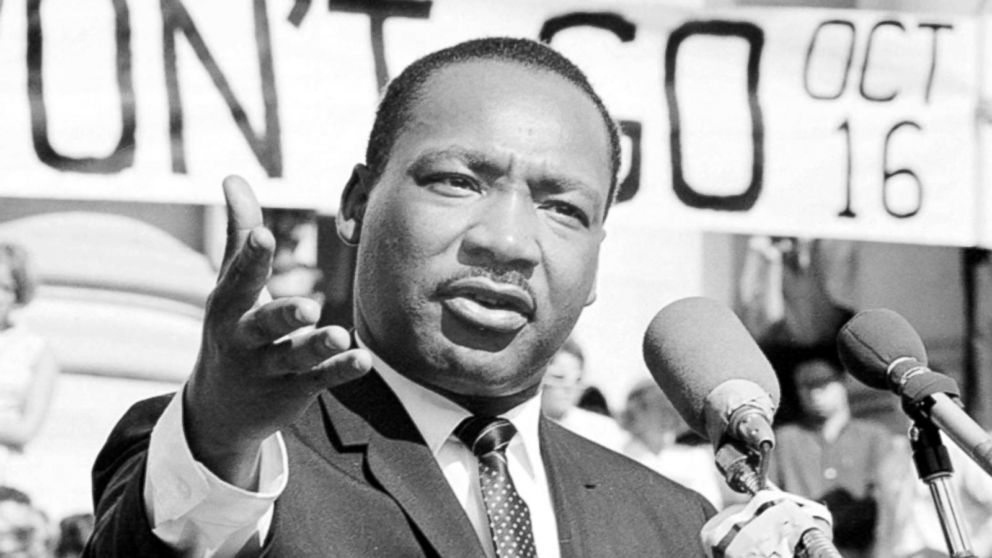

“It is an aspect of their sense of superiority that the white people of America believe they have so little to learn.” -Martin Luther King, Jr., 1967.

We appreciate that social science is full of highly complex ideas and phenomena, many of which some of our citizens and city officials are aware of, but have not yet needed to think deeply about. We understand that not everyone is a social scientist by profession, which is why we are offering our insight around these challenging social projects ahead of us. To be very clear, this is in no way a negative judgement of those who are new to studying race, class, and abolition, but simply an observation of the way that white, middle/upper-class, or other privileged people are required to operate in America. You may be familiar with W.E.B. Du Bois’ idea of “double consciousness,” or the idea that the oppressed are forced to understand not just their own worldview, but the worldview of their oppressors. White people are only required to understand the white worldview, while BIPOC must know their own worldview, and that of white people, simply so they might survive. This means that there is always something that people with privilege will need to work towards with an open mind to understand. The essays on this page have been written by IFR members and supporters, community members, and University of Iowa experts. If you would like any of the specific references cited herein, please leave us a message and we will send you the citation in APA format. Finally, if you have other questions about our policy support or other questions about race, abolition, class, etc., please send us a message and we will work with our team and University experts to answer them publicly.

Abolition 101

We come to you as activists and researchers in the spirit of the abolitionists that fought to get us a seat at this table. We invoke as our teachers and guides Harriet Tubman, W.E.B. Du Bois, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Angela Davis, and so many others—all abolitionists. Abolition is many things. At its core, it is a belief that punishment (i.e. police) is not a good solution to our community’s social, economic, behavioral, and interpersonal problems (Gilmore, 2020). It is a belief that in a democratic society, the people should get to choose how to construct their own sense of safety. It is a belief that safety should be shared, and not individualistic (Winder, 2020), which means that an entire community should be free to feel safe, not just its citizens who are white or financially secure. Abolition is the belief that a community’s sense of security can never exist when that security is enforced by violence and surveillance (Davis, 2020). It is the belief it is both inhumane and ineffective to respond to social harm with more punitiveness and more violence. Finally, abolitionists believe that the insecurity that exists in some neighborhoods is not the result of a cultural or biological flaw in a group of people, but because people are suffering and are searching for (often ineffective) ways to survive. The answer to this is not violence, more police contact, and more jail time, but additional supports like mental health treatment, better education, health care, affordable housing, and job opportunities (Vitale, 2017). Abolition does not just dismantle racist and classist institutions, but it simultaneously constructs new social systems that provide love and support for community members without social power, while providing healing and accountability when harm does occur (Davis, 2020). Media, politicians, and a racist history education have taught many of us, especially white and financially secure people, that police are synonymous with safety. The abolitionist question begins with: “Do we want police? Or do we want safety and security?” We have been told that there exists a “social contract” (Seigel, 2020) between the state and its citizens where we have exchanged our right to enforce rules in exchange for safety provided by police. We have agreed to give the police a “monopoly on violence,” so that when someone has broken a rule, the police have agreed to handle it on our behalf (Goldberg, 2019). However, this social contract has been broken for centuries. From police’s origination as patrollers of enslaved people, to their progression to reify Black oppression through racist laws during Reconstruction, to the widely publicized abuse during Jim Crow, to their integral role as the gatekeepers to the War on Drugs and construction of the prison industrial complex, it should be clear that the role of police has always been to entrench a racist capitalism in our society and convince our citizens that it is normal and natural (Davis, 2005, Fassin, 2020, Gilmore, 2007). For centuries, white and financially stable people have received the protection of the police within the social contract, while BIPOC and poor people have been the targets of the enforcement side of the “social contract.” Within abolition, we are not interested in “more humane” policing—which is to say “more humane” anti-Black, anti-poor violence. In the spirit of our abolitionist teachers, we understand the history of reforms, which have succeeded in placating the masses, but left the underlying institutions unchanged in their racist and classist functionality (Davis, 2020). Our demands for restructuring the ICPD involve getting off the “treadmill of reform” (Davis, 2020) and eliminating the entire structure that, from its first inception, under the threat of death, keeps us locked up and restricted to an existence that benefits only racial capitalism (Davis, 2005; Gilmore, 2007). We are aware that the pushback against these demands may be severe. But in the midst of America’s enslavement of Black people in the 18th century, the multi-racial Abolitionists group said, “We want [people] at this crisis who cannot be frightened from the advocacy of our ‘radical’ doctrines, because of their unpopularity...Let us not, then, grow weary, but believing that ‘whatever is RIGHT, IS PRACTICAL go forth…” (qtd. In Stauffer, 2009). Many people of Iowa City will believe our demands to be too radical and will push for another round of reforms. We will reject these reforms, not just because we have studied our history, but because we believe that whatever is right, is practical. The popular question “What will we do instead of police?” assumes that the current system is a good one (Kaba, 2017). If I am lying on my deathbed, I don’t question the efficacy of the doctor’s proposal to try something new that might save my life—I encourage it, because whatever happened before has brought me to death. We must remember that abolition already exists in neighborhoods all over this country. White families go months without seeing a police car drive by their house. White people go their entire lives without calling the police for protection. Why? Is it because white and financially secure people are superior and less prone to violence and crime? Or is it because the system has ensured that white and financially secure people in these neighborhoods have steady access to jobs, affordable housing, intergenerational wealth, education, and good health care? Even when young Johnny, who lives in the white suburbs, gets in trouble and goes in front of a judge, is he tried as an adult and sentenced to long-term punishment? Or is he offered another chance and asked to work within his community to make up for his misdeeds? This is the transformative justice that we must create together in Iowa City. Abolition must begin in Iowa City with less policing. It is the mere presence of police that harasses and intimidates BIPOC and poor people in Iowa City—something we see constantly, but have especially ripe examples the last several weeks as activists have been stalked, held up at gunpoint, arrested on spurious charges, and teargassed. While IFR protesters were shot with tear gas and flashbangs, the white supremacists across the bridge were gently escorted away. Immediately and in the long term, we insist on moving resources into areas that we know reduce crime and make community members feel loved and cared for. As we deconstruct the racist and classist system of policing, we demand to build up supports that we know work to provide safety and wellbeing: mental health treatment, education, affordable housing, job resources, physical health care, immigrant and refugee support, transportation, food resources, and more. During this project, we will also build new ways to protect each other as community members that do not rely on violence, such as mutual aid programs, transformative justice systems, truth and reconciliation commissions, and more. We will work with the entire city to decide what will allow us to feel safe. This is all to say that abolition is also a community project (Kaba, 2017; McDowell & Fernandez, 2018). This means that in a democratic society, the Iowa City community should not only have a say in how their safety is enforced, but that we are here to work with you to ensure a safer, more equitable city. We believe that we have a unique opportunity to be a model for many other communities, not just in this country, but across the world. This is a moment in racial history that will go down in the history books (Davis, 2020), and we are here as a community to ensure that Iowa City ends up on the right side of history. Over the past few weeks, we have received an outpouring of support for our demands—faculty members, administrators, and students from all over the University have offered their professional research support to reach abolition. Leaders of community-focused organizations who have been doing critical work for the community for decades have reached out offering their time and professionalism. And of course, as we all heard at the City Council meeting in June, the citizens of our city also have voiced their fervent support for our demands. We can all do this together and build a world where safety and security exist for our BIPOC and poor citizens in the same way that safety exists for our white and financially secure citizens today.

Systemic Racism

A topic that nearly all liberal white people hope to understand, but often don’t, is “systemic racism.” We have heard several city officials and citizens use this term, but it is clear that very few white people fully understand this tem. To be fair, it is a highly complex term that wasn’t widely used until Stokely Carmichael’s seminal book in 1967, and has since been studied in great depth. There is copious research that shows that a well-grounded understanding of systemic racism is the greatest differentiator between those who unintentionally enact racism and those who are anti racist, which is why we hope to use our expertise to shed some light. “We’re not in a situation here in Iowa City where we have police killing People of Color...I'm just trying to avoid conflation...our police are taking a lot, they’re receiving death threats, they’re taking a lot....” -A white councilor, June 30, 2020. In response to a challenge about the inherent danger that exists with police presence, a white city councilor made the above remark, which illustrates a misunderstanding of systemic racism on several different levels. Given that none of the other white city officials corrected this person, we can assume that this is a misunderstanding for all white city officials who were present for this meeting, as well as many others around Iowa City. First, we offer some brief definitions taken from decades of activists, scholars, and personal experiences from BIPOC people. Many people choose to differentiate between “individual racism” and “systemic racism,” although they often overlap, as we will show here. Liberal white people are often more familiar and more comfortable with “individual racism” since it encapsulates clearly prejudiced beliefs about racial superiority, and often relates to intentional acts of harm (Kendi, 2016). However, liberal white people often stop their education here and do not understand systemic racism because this progression in thinking showcases the white liberal’s role in racism, triggering defensiveness (DiAngelo, 2011; Jayakumar & Adamian, 2017; Leonardo & Zembylas, 2013; Unzueta & Lowery, 2008). Most scholars within critical race theory, psychology, and sociology include notions of power in their definition of racism and systemic racism (Goff, 2018; Jones & Carter, 1996; Smith, 2005; Solórzano & Yosso, 2016; Sue, 2003), noting that the unequal allocation of resources favors whites over non-whites and is sustained by the economic, political, social, and cultural control that whites have in this society (Hilliard, 1992). This means that systemic racism is the collection of institutions (health care, education, policing, politics, culture, etc.) that allows white people to either enforce their prejudiced beliefs, or to reap the rewards of a racist society without extra effort. The key here: power. All white people in US society have social power that comes from being white, and when they invoke this power in any of its many forms, they are contributing to racism. If the idea of having racial power is foreign, Janaya Khan describes it as “the freedom from having to think about things.” For example, white people do not have to worry about whether they were pulled over by police because of their skin color, don’t have to worry if their children will have school teachers who share their race, don’t have to worry if there will be any repercussions for not understanding the racial experience of others, etc. These are all examples of social power. Social power also comes in the form of class, employment, citizenship status, ability, gender, sexuality, and many other identities. The councilor in the exemplar quote above called upon the power of several forms of systemic racism in their response. While debating with a Black female councilor about the relationship between police in Iowa City and public safety, the white councilor invoked an image of the police as victims. This, of course, has never been true in US history, but illustrates a part of a long history of white people crafting images of Black people and their supporters as violent, and the abusers of power in uniform to be the victims (Kendi, 2016). Whether or not the police have received death threats is irrelevant to the racial order in Iowa City because the directionality of power and abuse of force has not changed, i.e. the individual detail is irrelevant because systemic racism is still ensuring that the police officers will be protected, both from outside violence and from repercussions of the violence they inflict on BIPOC people in Iowa City. The white councilor called upon the insurmountable power of multiple white systems (policing, history, & culture) in order to quiet the Black woman who was advocating for Black lives. This is an example of how white people (and white bystanders) employ powerful institutions to protect the status quo (e.g. policing, social perception, etc.) that perpetually allocates resources and opportunities to white people over BIPOC people. Systemic racism also looks at racial disparities. BIPOC people have a lower life expectancy, are twice as likely to die during childbirth (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014), and are admitted to prison on drug charges at 20-50x the rate of white people despite using and selling drugs at nearly the exact same rate (Alexander, 2012). White people have a median wealth of over 12x that of BIPOC (Economic Policy Institute, 2017) and are significantly more likely to attend and graduate college (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019). ICPD ask for probable cause searches for BIPOC at significantly higher rates than white people (KCRG, 2019), and Black people were arrested on marijuana charges at 5.4x the rate of white people in Johnson County (Iowa ACLU, 2020). We essentially have two choices when confronted with statistics like these: Do these disparities exist because 1) BIPOC people are biologically or culturally inferior, which leads them to poorer life decisions and life outcomes? Or, 2) There are systems in place that ensure that BIPOC people are denied equal access and opportunity to resources, resulting in unfavorable life circumstances and false, culturally-endorsed labels as criminals? The forthcoming change that is implemented by city officials must be at the systemic level. Anything less, is an endorsement of the status quo and support for the underlying racist beliefs that allow it to persist. We insist that our city officials not be the type of liberals that MLK (1967) warns us about, who offer symbolic and hollow support by saying “Black lives matter,” but instead do the work and make the sacrifices that allow Black lives to actually matter at a structural and tangible level. So far, we have heard City Councilors, the City Manager, and many other citizens and organizations use the term “systemic racism,” but we have only seen these people propose non-systemic, reformist solutions. To summarize, systemic racism is a difficult topic to understand because it deals with systems and institutions--entities that appear to be operating normally, but actually enact racism without clearly showing us any malintention. The reason a person doesn’t see the racism within a system is likely because they are not negatively affected by it. On June 6, a city councilor told the Speak Up, Speak Out crowd, “I love the police.” About a month later, on July 7, one councilor stated: “In over 50 years of living here...I always found the officers to be helpful and professional in carrying out their duties and I can say I’ve always been proud...of the work they’ve done...to provide a safe community.” These views attempt to look at individual police officers and personal interactions with them, which act to mystify the larger system of policing. Sentiments like these are the precise reason that we evolved from our understanding of “individual racism” to a more nuanced understanding of “systemic racism.” Individualism and its ideologies are how we will fail--we must reject the idea that individual actors cause harm and instead look at the system that allows them to exist. We encourage our city officials to reflect on the complex social education that lies ahead of them if they are to truly understand the nature of the problems in Iowa City.

Equality over Equity

One of the leading modern scholars in race is also the seminal author in colorblindness, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (Bonilla-Silva, 2018). One of his dimensions of colorblindness is “abstract liberalism,” which is the way that liberal white people seek out social ideology that appears fair and locates them as “good” relative to the political right, but actually lacks critical depth and only further entrenches racist structures. One way that white liberals do that is with the belief in equality instead of equity. “We have to remember that we were elected as city council members for everybody, not just the IFR”-A white city councilor, June 30, 2020 The above sentiment was echoed by several city officials, and while true from a political standpoint, lacks the depth necessary to understand the social complexity of the current moment. While it is, of course, the job of city government to intake the opinions of every citizen that they represent, it would be reductive and oppressive to weigh those opinions equally. IFR is asking that BIPOC, young, and poor people of Iowa City have more weight in the decision making about the future of policing than those who are privileged, employed, white, citizens, etc. A more pointed question that is needed might be, “Why should BIPOC people, young people, and poor people have more of a say than white people in how we restructure our police department?” This leads to a discussion of the white liberal’s preference for equality over equity. Equality and equity are two ways to ensure everyone is treated fairly, however, these two strategies differ in their approach to achieving what it means to be “fair.” Equality has to do with treating people the same regardless of circumstances or individual differences (Rescher, 2002). Equity promotes fairness by applying rules differently to different groups of people based on circumstances, with the goal of achieving equal opportunity for everyone qualifying for the given opportunity. Equity seeks to provide a level playing field by giving everyone equal access to resources and opportunity to succeed (Rescher, 2002). In our circumstance, it reasons that the oppressed group needs to have their voices centered and elevated in order to achieve an equitable outcome. This is why the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission is widely believed to have been successful (Clark, 2012; Kilgore, 2016). A common question asked in this circumstance is, “If you want to know about antisemitism, do you ask the Christian or the Jew? If you want to learn about sexism, do you ask men or do you ask women and non-men?” Similarly, we are asking to learn about police violence in Iowa City. Do we need the opinions of white or middle and upper class people, the vast majority of whom have never been subject to police violence or surveillance, and the ones who have crafted and supported the system as it exists today? Or do we need to privilege the viewpoints and voices of BIPOC and poor people, who have been subject to intergenerational state violence and surveillance since they were young children? Further, we acknowledge that young people have historically been pushed to the margins during progressive movements because they often represent a threat to the status quo that is upheld by people in positions of community and government power (Davis, 2016; el-Shabazz, 1991; Kendi, 2016). Civil rights leaders widely critique people in positions of power for excluding the progressivism of young people, and we ask our city officials to not make this same mistake. We further implore the necessity of centering those whose voices have historically been muted in Iowa City: our immigrant and refugee community, homeless, differently abled and non-neurotypical, minoritized sexual and gender identities, and other marginalized communities. These people may not have the recognizability and social capital of our “community leaders” and prominent organizations, but we believe they deserve their voices to be centered. The forthcoming changes in policing in Iowa City will not reduce the safety and security enjoyed by white and financially secure people. They will still have their health care, education, intergenerational wealth, social standing, and cultural centrality. They will merely lose one primary force that enacts white supremacy on their behalf. Therefore, it is essential to focus on the voices and opinions of the people who have been most affected by the violence we are hoping to change.

“ACAB”

We are aware that many city officials and citizens have taken offense to our chant, “All cops are bastards.” While we understand this is an upsetting idea for many people to hear, we hope to explain the scholarly and critical importance of this chant herein. “The theory of the ‘absolute evil’ of the colonist is in response to the theory of the ‘absolute evil’ of the native” -Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth Here, Fanon points out the myopic nature of taking offense to “ACAB.” If one is offended by “ACAB”, they have likely chosen to ignore that the person saying “ACAB” has already been labeled as “absolute evil” by those with a badge and a gun. BIPOC people are not the ones terrorizing the lives of others--the directionality of state power doesn’t allow them to--so to spend our time feeling sorry for the police illustrates a misguided understanding of both history and our present reality (Baldwin, 1972; Khan-Cullors, 2017; Shakur, 1988). We cannot spend time being offended by words while these words merely reflect the daily danger that state power the lives of Black and poor people in Iowa City. James Baldwin writes in No Name in the Street (1972) that the Black American quite literally cannot afford to differentiate between one cop and another--that their violence towards Black people is so profound and indiscriminate, that it is ignorant and dangerous to spend time searching for the “good ones.” This is not to say that we believe all individual cops are bad humans who hate BIPOC and poor people. This is to say that the idea of “not all cops are bad” is a reductive argument that deflects from the central point of what BLM stands for: the rejection of systemic racism. This tells us that anti-racism is not about teaching individuals to be kinder to each other, it’s about undoing the interlocking web of institutions and cultural beliefs that ensure BIPOC and poor people aren’t given an equal chance to life. Herein lies the key differentiation between systemic racism and individual racism. When we discuss other eras of state violence and oppression, do we take the time to wonder who the good actors were? Should we search through all the 18th century enslavers and find the ones who tried to be good to their enslaved people? Should we sift through the ranks of Nazis to find the “less guilty” ones who drove the trains to the camps without paying attention to who or what they were transporting (Cohen, 2001)? Of course not--it is not a useful argument because of the massive scope of the oppression that was happening. Of course there were “good,” well-meaning people who tried their best in those circles--people who were only going along with the social order that they were raised in, or people who were lost and searching for an identity. But none of that relieves them of their role in horrendous epochs of systemic racism. When we are faced with a system that is so thoroughly violent and racist and classist, it’s no longer about the individual, but about the system that they uphold. Further, Black and poor lives cannot afford to be interested in the good intentions of the individual “good” cops because we have been shown over and over again that they choose silence over equity. MLK wrote, again in 1967, “To ignore evil is to become an accomplice in it.” If good cops exist, then why did none of them stop the bad ones from firing flash grenades and pepper spray at us in early June? If good cops exist, why did none of them stop the bad ones who were following us home from the protests and drawing their guns on us? If good cops exist, why did none of them step up when Mazin was arrested and taken out of the county as a political prisoner? If good cops exist, why didn’t one of them take off their riot gear and stand with us as we pleaded for Black lives to matter in Iowa City? If good cops exist, where were they when one one of our activists was sexually assaulted by one of the bad ones? “Now, this is the evidence. You want me to make an act of faith, risking myself, my life, my woman, my children, on some idealism which you assure me exists in America, which I have never seen?” -James Baldwin, 1969 So, we ask you: are you asking us to make an act of faith that there are good Iowa City police officers, given not just the abuse we have seen in the past few weeks in Iowa City, but within the thousands of stories that you have yet to hear which span our entire lives? Simply speaking, we have yet to see the “good cops” that you assure us exist. We have only seen violent offenders, their bystanders, and an entire system that supports them both. Even if the good ones do exist, the scope of the violence that exists in the world of BIPOC and poor people in Iowa City is too profound--we must focus on the entire system.

Addressing Other Questions:

What about the very dangerous criminals who kill, sexually assault, etc.? This is an important question that we think about constantly, and a question that we know we have a better answer to than what exists now. Just as in many other places within abolitionist theory, we have to unravel the false connection that we have been taught, which says that police are equal to safety. While this is true for most white and financially stable people, this is not true for BIPOC and poor people in Iowa City. When we talk about “what about the violent offenders?” we need to realize that the most violent and harmful members of our society are the ones with power. These are the ones who allow homelessness to exist while others sit comfortably in their 3-story house. These are the people who ensure police are well funded while mental health care and job support programs receive the city’s budget leftovers. The people with guns and badges are the ones who harm us with more frequency and less repercussions than anyone else. Further, despite the popular rhetoric, police do not protect us from harm. While many white and financially comfortable people feel comfortable knowing that police will come to them if they ever need to call, we have countless stories of Iowa City police failing to respond to calls for help simply because the address given is not in the right neighborhood. Even if Iowa City police did decide to come to our aid, they would not be preventing crime. Copious studies have been undertaken to determine how police activity manages crime (Kaba, 2020; McQuade, 2019; Vitale, 2017), and what they’ve found shows us how little police actually do to protect us. As little as 6% of an officer’s time is spent on something that turns out to be actual criminal offenses, and the average police officer arrests someone only once every two weeks. One study in a “high-crime” area of New York City found that 40% did not make a single felony arrest in the entire year of the study. By the police’s own definition, about 80% of their time is spent on non-criminal related activity (Kaba, 2020; McQuade, 2019; Vitale, 2017). Quite simply, the vast majority of policing does not relate to criminal activity, does nothing to keep us safe, and only enforces minor laws that serve to disadvantage BIPOC and poor people in Iowa City. While our city provides very sparse information on police activity and funding, it is clear that they are highly ineffective at preventing crime and solving cases. Further, police do not enforce the law equally and they are not accountable to that law. The police exist as “order maintenance” rather than law enforcement. People spoke widely about IFR protesters being “dangerous” or causing “safety concerns” by going onto the highway recently. But the only injuries that were sustained these past months were by protesters after the police used weapons against them. Safety was never jeopardized until the police were present because instead of protecting us, they insisted on “restoring order” in a way that protected their power and social position. We have also seen evidence that the police are not accountable to the law. Despite using weapons on a group of peaceful people who were kneeling on the ground with their hands up, no officer will be reprimanded for their violence against our group. When the governing state investigates the body that enforces state power, there can never be justice. So, to this question, “What about the dangerous person?” The dangerous person is the police. The mass murderer is the police (who kill exponentially more people than random killers), the burglars and robbers are the police (thanks to civil forfeiture laws), the rapist is the police (our protesters have suffered sexual assault at the hands of our police, Women and non-binary People of Color have been shown to be the favorite targets of police sexual assault: Fischer, 2020, and a 2014 study outlines this hidden pandemic in detail: Stinson, Leiderbach, Brewer, Mathna, 2014). If the idea that the dangerous person is the police feels new to anyone, it is most likely because they have not been in close enough relationship with BIPOC and poor people in Iowa City.